My World of Flops Racially Problematic Case File #168 The Travolta/Cage Project #41 White Man's Burden (1995)

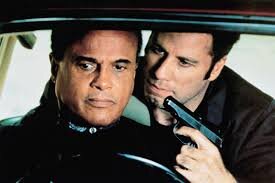

Name a more racially charged duo!

Now, more than ever, filmmakers need to be careful and deliberate when dealing with race, particularly in a metaphorical or allegorical fashion. You simply can’t be too precious or cute when tackling such an explosive, emotionally loaded subject or you end up trivializing an issue at the very heart of our current national discourse.

Filmmakers that want to use film to articulate something profound and important about our nation’s complicated and fraught racial history must walk a tricky, if not impossible tonal tightrope.

The staggeringly misconceived 1995 racial allegory White Men’s Burden attempts to walk this tightrope. Instead it falls off gracelessly in the first few seconds, busts its head wide open then lurches about, bleeding, dazed and confused, for eighty-nine excruciating minutes.

In order to pull off its premise, White Man’s Burden would need to be agile and sophisticated. Instead it’s a lumbering elephant of a cinematic mistake that stomps about loudly, accomplishing nothing.

White Men’s Burden takes place in an alternate universe where the longstanding racial dynamics of our country have been reversed. African-Americans have money and power, and live in gated communities far away from impoverished white folks.

On the airwaves, white faces are few and far between, police brutality negatively affects caucasians rather than people of color and, needless to say, all the superheroes are super soul brothers.

White Men’s Burden asks what it adorably seems to think are provocative questions. What it we lived in a world with upscale neighborhoods full of rich, powerful black people? Alternately, can you even imagine what it would be like if there were poor white ghettoes full of desperate, uneducated white people prone to crime and hopelessness? Lastly, White Men’s Burden asks what it would be like if someone who looks, talks and carries himself like Harry Belafonte was rich, powerful and distinguished.

These thought exercises aren’t too difficult for me because I live in Atlanta, where there is a huge, thriving black upper class full of millionaires and the occasional billionaire and also in the world that I inhabit a man who looks, talks and carries himself like Harry Belafonte (because he is Harry Belafonte) is extraordinarily rich, powerful and distinguished, and has been for longer than most people have been alive.

There are no micro-aggressions in White Men’s Burden or even macro-aggressions. Instead there are what I will call Monster Aggressions that reflect racism in its purest, ugliest, most blatant, heavy-handed form. A noble but angry white man is beaten down by the police because he ostensibly looks like the suspect in a string of armed robberies while other destitute white folks look on. Our hard-working, fundamentally decent white hero gets unceremoniously fired from a job he works hard at for looking at a prominent black man’s wife.

Black cops tell the white man and his family that they’re being evicted and have five minutes to round up all of their belongings before they’re uprooted forever. Thaddeus Thomas (Harry Belafonte) A powerful black man, converses with the well-heeled black folks at a dinner party about the genetic inferiority of white people, how they are so hopeless and devoid of fathers that they are beyond redemption.

Racism in the United States is toxic and pervasive. But it’s also far more complicated than this bizarre exercise in metaphorical minstrelsy would have you believe.

A defeated and overwhelmed Travolta slathers on allegorical blackface for the thankless role of Louis Pinnock, a hard-working, overwhelmed husband, father and factory worker just trying to get ahead in a black man’s world.

Louis asks his black boss for a promotion to foreman. When his superior doesn’t agree instantly, Louis asks if he thinks he’s behaving in an “uppity” fashion, a cringe-worthy exchange that epitomizes the movie’s clunky obviousness.

Instead of a promotion, Louis ends up getting fired when he’s mistaken for a “peeping Tom” when he makes the mistake of looking through the window of the Thomas home and catching Thaddeus’ wife Megan (Margaret Avery) in a state of undress while delivering a package.

Louis tries to appeal directly to Thaddeus for his job back but the wealthy bigot dismisses him as just another shiftless white man who thinks the world owes him something. In his desperation, Louis holds the older man hostage and takes him on a guided tour through the waking nightmare of a poor, crime-ravaged inner city full of violent, profane white people and teaches him about the folly of judging another human being on the basis of the color of their skin rather than the content of their character.

White Man’s Burden ends with its white hero sacrificing his life in a Christ-like fashion for a black man that has treated him, and all other white folks, terribly over the course of the film.

Of course in this world Louis is coded as being culturally black so it falls upon him to teach an exemplar of unexamined privilege about the evils of racism before dying a hero’s death.

Instead of subverting or challenging or critiquing hackneyed racial tropes, White Man’s Burden confusingly makes its protagonist a singularly unpalatable, offensive combination of White Savior and Magical (Faux) Negro.

White Man’s Burden belongs to a strain of idea-intensive science-fiction that individually and collectively ask how white people would feel if, through some crazy twist of fate, they ended up suffering the kind of vicious racism that they subject other races to in real life.

I didn’t know White Man’s Burden was even in contention for any Golden Raspberries!

This message movie without a message argues that white people sure would hate it if black people treated them the way white racists treat black people. Sadly, that’s about all White Men’s Burden has to say.

White Man’s Burden’s provocative but ultimately unpalatable premise puts writer-director Desmond Nakano in an impossible position. If he hammers home the ways in which the poor, oppressed white people of his world suffer in the EXACT same fashion black people do in our world then he risks being didactic, ham-fisted and painfully on the nose.

But if Nakano abandons the alternate universe reverse racial dynamic for too long it begins to call into question why they bothered with it at all. White Man’s Burden could just as easily be about a poor white man taking a rich black man hostage and retain the same dynamic without bringing in a tricky science-fiction conceit the movie itself doesn’t seem to understand.

Anti-black racism in the United States has a very specific, concrete history and context rooted in centuries of slavery and the brutality of the Jim Crow era. Without this real-life context, White Mans Burden feels shallow and offensive, not to mention hopelessly removed from the genuine pain that should be at its core.

White Man’s Burden should vibrate with contemporary relevance and timeliness. We are, after all, in the midst of a massive cultural reckoning over the role racism plays in American society, particularly where police are involved.

A movie that’s about nothing but racism should be perversely, insanely timely. Alas, White Man’s Burden has just as little to say about American racism as it did back when it was politely ignored during its whimper of a theatrical release back in 1995.

Time has not redeemed White Man’s Burden; it remains eternally, perpetually clueless and useless.

Failure, Fiasco or Secret Success: Failure

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace

Also, BUY the RIDICULOUSLY SELF-INDULGENT, ILL-ADVISED VANITY EDITION of THE WEIRD ACCORDION TO AL, the Happy Place’s first book. This 500 page extended edition features an introduction from Al himself (who I co-wrote 2012’s Weird Al: The Book with), who also copy-edited and fact-checked, as well as over 80 illustrations from Felipe Sobreiro on entries covering every facet of Al’s career, including his complete discography, The Compleat Al, UHF, the 2018 tour that gives the book its subtitle and EVERY episode of The Weird Al Show and Al’s season as the band-leader on Comedy Bang! Bang!

Only 23 dollars signed, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here