Christopher Guest's 1989 Debut The Big Picture Is an Irresistible Outlier in its Creator's Career

Christopher Guest is no mere filmmaker. No, the man who brought the world Waiting for Guffman and Best in Show, among other cult delights, is a sub-genre onto himself. The “Christopher Guest movie” is more than just a movie directed by the veteran filmmaker, actor and musician. No, when we talk about a Christopher Guest movie, we’re generally talking about films that are almost completely improvised off a loose structure created by Guest and longtime collaborator Eugene Levy. We’re talking about movies that take the ramshackle but useful form of mockumentaries, a form Guest all but owns, despite, or perhaps because, of the preponderance of imitators and wannabes trying to replicate his success.

Guest’s films are similarly defined by the beloved roster of familiar faces that pop up in film after film, national treasures and genius improvisers like Levy, Guest himself, Fred Willard, Catherine O’Hara, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer, Bob Balaban, Jane Lynch, Larry Miller, Parker Posey, Jennifer Coolidge, John Michael Higgins and Michael Hitchcock.

With a repertory company like that is it any wonder Guest is just about the most consistent comedy director around?

Guest’s 1989 directorial debut The Big Picture is a fascinating anomaly in Guest’s career. While he cowrote (with old pal Michael McKean and Michael Varhol, who co-wrote Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure) and directed it, and it explores many of the filmmaker’s pet themes, particularly the runaway egos of show-business folk, it otherwise bears few, if any, of the hallmarks of his later work.

For starters, the movie is not a mockumentary, nor is it overwhelmingly the product of improvisation and ad-libbing. And while McKean has a nice, understated role as the protagonist’s best friend and cinematographer, the repertory company that would become synonymous with Guest is otherwise absent.

Guest’s signature films are ensemble comedies but The Big Picture is focussed intently on protagonist Nick Chapman (Kevin Bacon) a hotshot film school graduate whose pretentious, award-winning short film briefly ignites the feverish, if short-lived attention, of a slew of Hollywood parasites.

Nobody seems to have the time, or the patience, or the willingness to watch even a short film, but that does not keep them from hailing him as a genius, sight unseen. In a scene-stealing supporting turn, Martin Short plays Chapman’s daffy agent, who tells his young, impressionable, easily swayed client, “I don’t know you. I don’t know your work. But I think you’re a talented young man and I’m never wrong” as if the first half of that statement doesn’t completely invalidate the second part.

In The Big Picture, as in Hollywood, the less informed people are, the more authoritative they seem. That’s particularly true of our hapless, overwhelmed hero’s would-be dream-maker, Allen Habel (the late, great J.T Walsh in one of his best performances and certainly his funniest), who loves Chapman’s arty, pretentious vision for a dour, theatrical and pretentious, black and white art film about a love triangle among forty-somethings that plays out against the snowy backdrop of a brutal winter and a non-existence score or soundtrack that stands in for God’s icy silence.

The executive only has a few minor suggestions. Do they have to be in their forties, when kids between the ages of 14 to 24 buy the most movie tickets? And why does it need to be a heterosexual love triangle involving two men and a woman when the executive is totally turned on by the idea of a bisexual love triangle involving hot, not to mention commercial, girl-on-girl action? Also, why does it have to be in black and white, and in a bummer of a season like the winter? What about Summer? Isn’t that just plain more fun? Finally, what if God’s stormy silence was replaced by fifteen to twenty top pop hits?

Early in The Big Picture, a cinematic true believer at the National Film Institute ceremony where Chapman wins the big prize quotes Frank Capra as arguing, “Don’t compromise. For only the valiant can create. Only the daring should make films. Only the morally courageous are worthy of speaking to their fellow men for two hours in the dark. Only the artistically incorrupt will earn and keep the people’s trust.”

These words ring with bitter irony even at the very beginning because The Big Picture, like so many Hollywood comedies, is a comedy of corruption. We know going in that in our world, the artistically incorrupt never get to make movies, for that is the exclusive realm of the compromised and corruptible.

Sure enough, The Big Picture is about a naive innocent from the Midwest who comes into the world of studio filmmaking full of hope and enthusiasm and discovers that compromise and moral, spiritual and creative corruption are endemic to filmmaking.

Chapman sells out his vision pretty quickly for the sake of a big payday, sure, but also for the thrill and ego-boost of being able to realize his dream of making his movie while the rest of his film school classmates are still floundering. These classmates include Jennifer Jason Leigh as Manic Pixie Dream Girl Lydia Johnson. She’s the kind of quirk machine who lives in an old mannequin factory, which she has decorated to look like a bohemian, hipster version of Pee-Wee’s Playhouse. Lydia casually offers her friends Pez from Pez dispensers and cheers up our sad-sack hero when he’s at a low ebb with her irrepressible lust for life and free-floating creativity. That might sound insufferable but Leigh makes it surprisingly palatable, although it’s probably a good thing she’s a minor supporting character rather than a lead. A little of Lydia’s nuclear-level quirkiness goes a long way.

Nick is willing to compromise and corrupt his artistic vision until his Ingmar Bergmanesque, very adult art film has somehow becomes a wacky, sexy teen romp called Beach Nuts that may also involves ghosts, because why the hell not? When Habel is ousted as head of the studio Chapman suddenly finds himself without a champion, without a job, and without a deal.

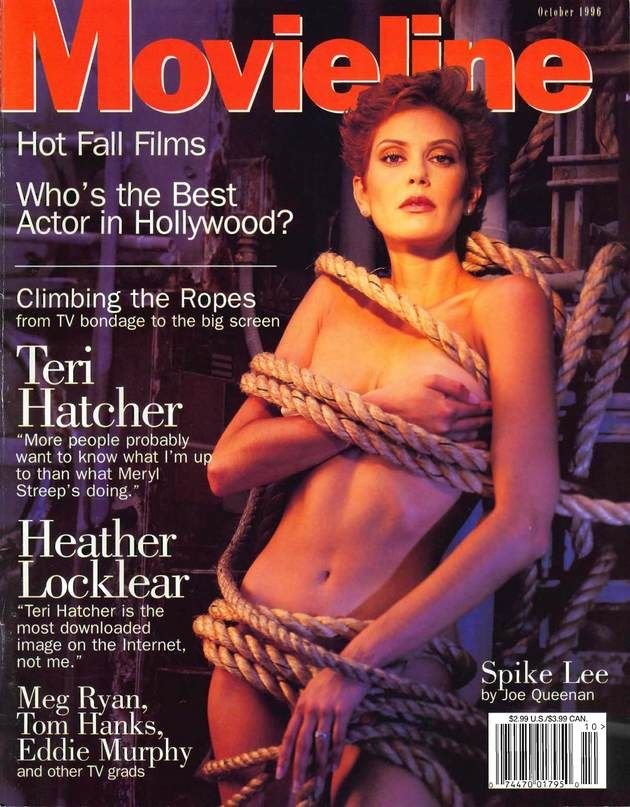

Nick lets himself be corrupted by the empty promises of show-business and the hot-blooded come-ons of scheming, ambitious starlet Gretchen (a young Teri Hatcher, oozing sex), much to the displeasure of his long-suffering girlfriend and conscience Susan (Emily Longstretch). Nick makes a gradual, incremental transformation from starry-eyed, serious film student to archetypal Hollywood phony before the ugly, fickle realities of the business bring him crashing down to earth.

At a certain point, it seems like Nick would be willing to direct a porno or a snuff film solely for the sake of actually getting something made. He’s overdue for a humbling and the film provides him with just that, as he goes from being the recipient of exquisitely insincere show-business flattery to getting turned down for waiter jobs before a chance encounter with quirky, selfless Lydia helps Nick get his groove back, personally and professionally.

The Big Picture ends as yet another Hollywood riff on The Emperor’s New Clothes, a classic tale that always has enormous resonance in show-business.

Tonally, The Big Picture is more understated and restrained than the Christopher Guest pictures that would follow, with the possible exception of his ill-fated, little-loved 1998 Chris Farley/Matthew Perry comedy Almost Heroes, which I have not seen. Bacon makes for a solid straight man and audience surrogate. His innate likability makes the character relatively sympathetic even as he consistently behaves selfishly and unsympathetically.

The Big Picture lets its self-absorbed protagonist off a little easy, even if his success at the end of the film is built upon hot air, gossip and that ineffable yet powerful entity known as “buzz” as opposed to his actual accomplishments.

Guest’s insightful and consistently funny exploration of the way Hollywood corrupts easily corruptible quasi-innocents like Nick Chapman deservedly got good reviews upon its release, only to be all but abandoned by Columbia, the studio that made it, after David Puttnam, the executive who green-lit it, was fired.

In that respect real life imitated reel life, and Guest, like Nick, found himself suddenly without a champion. That bitter twist only adds to the welcome verisimilitude of a rock-solid debut that has never quite gotten the attention it deserves, in no small part due to the very Machiavellian show-business game-playing The Big Picture so adroitly sends up.

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only! at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

PLUS, for a limited time only, get a FREE copy of The Weird A-Coloring to Al when you buy any other book in the Happy Place store!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!