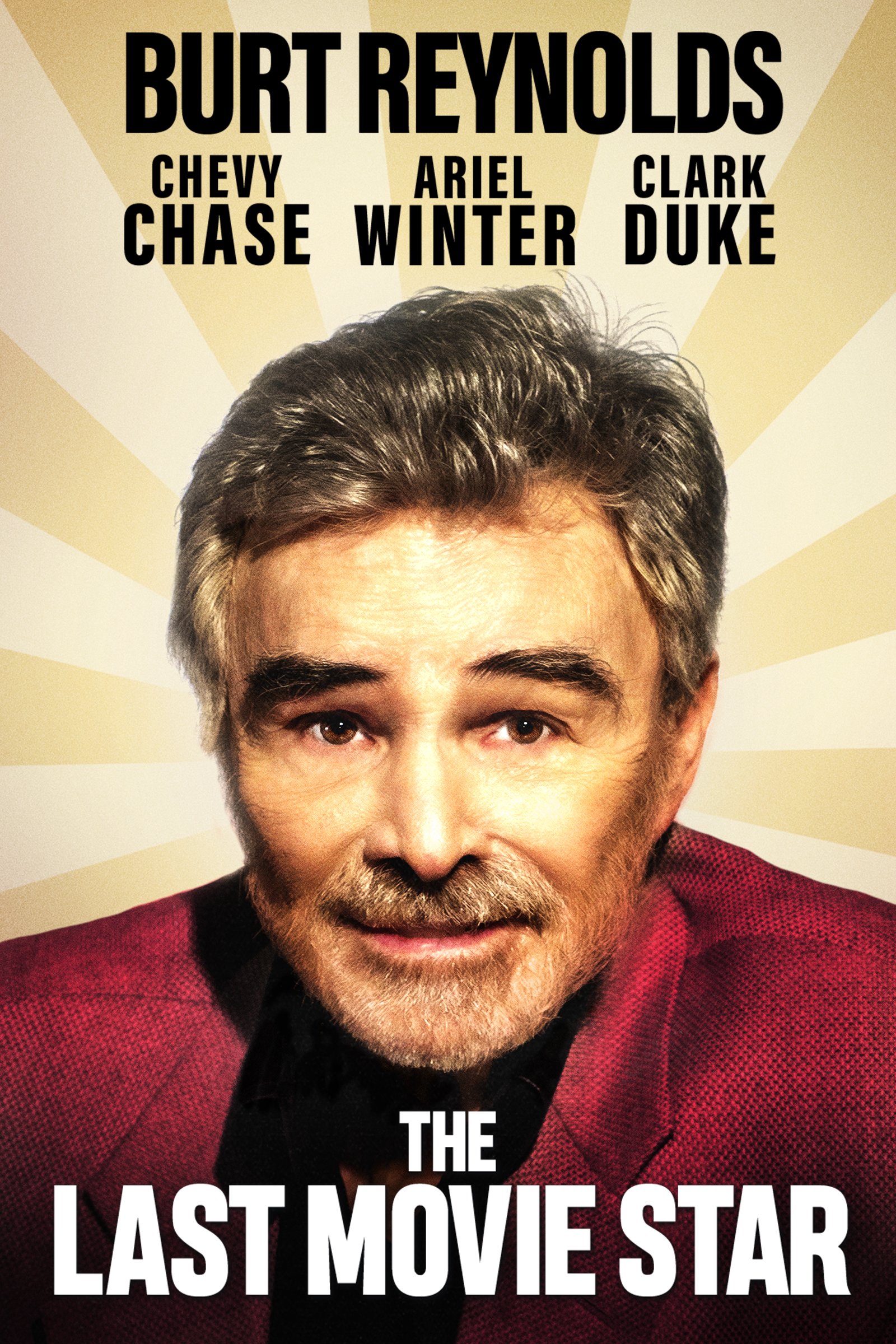

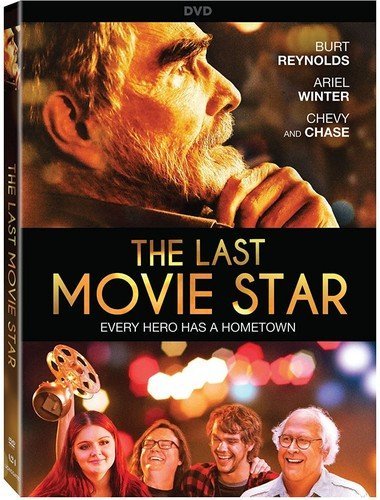

2018's Poignant and Powerful The Last Movie is Star Burt Reynolds' Lost in Translation

When Burt Reynolds died at 82 it had been a good four decades since his astonishing Carter-era heyday, when he was nothing less than the biggest movie star in the world, the world’s sexiest man and embodied what a sizable portion of the American public thought a man should be.

But it had also been a good two decades since Reynolds’ equally remarkable mid-1990s comeback, when he reinvented himself as a hilarious and fearless silver fox of a character actor with standout turns in Striptease, Citizen Ruth and, most famously, 1997’s Boogie Nights, which won him his first and only Academy Award nomination.

Boogie Nights should have been the catalyst for an exciting new phase in Reynolds’ career where he’d continue to pick up killer roles from admiring auteurs who grew up worshipping him. Alas, Reynolds was not always the best custodian of his extraordinary talent, as evidenced by the fact that he chose to make Stoker Ace over Terms of Endearment, where he would have played the role that won Jack Nicholson an Academy Award, and very publicly wrestled with regret over making, in Boogie Nights, one of his very best, if not his best and most beloved film.

Even Burt Reynolds fans would be hard-pressed to identify many of the films the Smokey and the Bandit exemplar of hairy-chested, All-American macho made after Boogie Nights, many of which went direct to video, or, if they were theatrically released, relegated Reynolds to the sideline with supporting roles, like his turn in the Adam Sandler remake of his own The Longest Yard.

Reynolds’ career was full of questionable choices but towards the end of his life he began to mount another comeback. Reynolds had been cast in the role of George Spahn, the owner of the Ranch where Charles Manson and his associates holed up in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and tackled the demanding and deeply personal lead role of Vic Edwards, an unmistakably Burt Reynolds-like movie star facing down a lifetime of regret and missed opportunities in cult filmmaker Adam Rifkin’s lovely character study/valentine to his lead actor, The Last Movie Star.

Rifkin launched an underdog campaign to garner awards attention, most ambitiously the holy grail of a posthumous Academy Award nomination or Oscar for his late, lamented star. It’s easy to see why. Reynolds delivers a virtuoso performance here that favorably recalls similarly masterful, late-in-life, Oscar nominated turns like Bill Murray in Lost in Translation and Bruce Dern in Nebraska.

Reynolds wasn’t just a good-looking guy; he was damn near the best-looking man of his time. Yet in The Last Movie Star he boldly looks and acts his age. His mind is still sharp and lively but that famously buff athlete/stuntman body, so conditioned to taking pains, to absorbing blows on a football field or a TV or film set, is frail and hunched over, brittle and aged.

Reynolds delivers a performance devoid of vanity or pretense. He’s one of those magical human beings who can appear in movie after movie, many of dubious quality, without ever seeming to act. Instead, Reynolds existed onscreen. He lived. He was so natural that it was easy to lose sight of the craft of Reynolds’ work, the artistry.

Particularly in its powerful third act The Last Movie Star gives Reynolds big Oscar speeches and moments of tremendous gravity and sadness but in many of the film’s most hypnotic and moving moments, Reynolds doesn’t seem to be doing much at all. The movie is never more compelling, for example, than when it just follows its octogenarian star as he wanders through a supermarket and then comes home to an empty house much too big and lonely for a man his age.

His character Vic Edwards receives an invitation to personally pick up a Lifetime Achievement Award from a Nashville film festival that is genuine in its enthusiasm for film and Vic but otherwise lacking in honesty, ethics and anything resembling a budget. Also, it’s not really a film festival so much as a bunch of film geeks hanging out and watching some movies.

Badly run by affable film geeks played by Clark Duke and Boyhood’s Ellar Coltrane, the wannabe festival lures the depressed screen legend to their beyond modest little soiree under false pretenses. The well-meaning but cash-strapped film buffs try to pass off a few screenings in the back of a bar as a film festival and a room in a rundown motel and rides in beat-up old car driven by Lil (Ariel Winter), a temporary assistant in the midst of a romantic breakdown that keeps overlapping and interfering with her quasi-professional obligations, as first class accommodations.

The prickly former movie star understandably rebels against his hosts, their lies and their cockamamie “festival” and decides to have his equally pissed-off driver take him back to his home town to handle a little unfinished business and reflect back on the man that he used to be and the people he left behind in his lust for fame and glory.

The Last Movie Star gives its hero a redemptive arc as he travels from curiosity to aggravation to explosion and finally to understanding, reconciliation and appreciation for the life he’s lived and the people who’ve loved him even when he was incapable of loving himself. It’s a performance so monumental that it’s bigger than the modest little sleeper it so confidently anchors. The Last Movie Star is laser-focused on Reynolds, but Rifkin has nevertheless surrounded his star with a top-notch supporting cast that includes Chevy Chase as our elderly protagonist’s longtime pal and confidante.

In 1978, the idea that Burt Reynolds and Chevy Chase would star together in a movie that would take a long time to get financed, and then struggle to be seen, would be inconceivable. But as The Last Movie Star illustrates, time and age have a way of humbling even our greatest and most popular artists and entertainers.

The past takes on a physical as well psychological presence here in the form of clips from throughout Reynolds’ career not just from his movies and television shows but also from appearances on The Tonight Show opposite Johnny Carson where he flexed a goofy sense of humor as appealing and ingratiating in its own way as his matinee idol looks and charisma.

In the film’s most technically and stylistically ambitious and audacious sequences, Rifkin uses green screen to put his eighty-something movie star into the same frame and the same scene as iconic early sequences from Deliverance and Smokey and the Bandit, using computer wizardry to plant the older, regret-filled Reynolds in place of Jon Voight and Sally Field respectively so that the glorious, idyllic past, when Reynolds was so beautiful it damn near hurt, can interact with the present, when he’s diminished by age and the cruelty of time but still a raging force.

Truth be told, the gimmickry of the Deliverance and Smokey and the Bandit scenes distract from some of the raw emotion. The movie is on surer footing during a number of lovely, heartbreaking little and big moments where Reynolds luxuriates in getting to inhabit, with his full soul and all of his talent, the kind of juicy, emotional, vulnerable, funny and achingly sad role he didn’t get to play anywhere near often enough in a career where he was too often typecast as a macho, gum-smacking action figure of few words and little depth.

It’s impossible to imagine any other actor as Vic. Indeed, Rifkin would not have made the film without Reynolds. The movie is a wonderful vehicle lovingly custom-crafted for its star but it’s also a tender meditation on Reynolds and a form of masculinity he embodied in its purest form that now seems lost to the ages now that the Cannonball Run star is no longer with us.

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out and it is magnificent!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.