Aaron Sorkin's Insane Suggestion that Democrats Nominate Mitt Romney is the Only Excuse I Need to Rerun This Piece on Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip

When Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip and 30 Rock premiered, the consensus seemed to be that the Tina Fey–created workplace comedy about the zany goings-on at a Saturday Night Live–like sketch show stumbled out of the gate while Aaron Sorkin’s much-hyped drama soared.

When the shows ended their respective runs, history had rendered a much different verdict. 30 Rock was rightly hailed as one of the best and most influential television comedies of all time, a whip-smart show-biz satire that forever changed the look, feel, and pace of sitcoms, while Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip went down as one of television’s most spectacular disasters.

Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip began and ended its brief, unfortunate tenure while I was employed as a staff writer for the entertainment section of The Onion. I was, therefore, in a privileged place to judge the accuracy of its portrayal of the art and craft of comedy.

But you do not need to be immersed in the world of funny people for Sorkin’s melodrama to ring hilariously false. You don’t have to know comedy writers to know that they don’t talk and act like the characters in the show because nobody talks or acts like the satirical saints of Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip.

Even the wonkiest bullshit detector would be able to detect that Sorkin’s breathlessly preachy, didactic exploration of the society-saving power of mediocre sketch comedy was bullshit.

But comedians and comedy writers were particularly fascinated by how desperately Sorkin tried to capture their milieu and how miserably he failed.

Sorkin was a television and film veteran with a gift for writing snappy, rapid-fire banter. Yet, he somehow labored under the delusion that funny people are mostly concerned with proving their moral righteousness and lecturing each other and the ignorant masses.

Sorkin approached an innately irreverent sphere from a place of near-religious reverence. Comedy wasn’t just important to Sorkin. It was sacred. It was church. It was religion. It was certainly nothing to laugh about.

It takes a writer and creator of Sorkin’s extraordinary talent to create something as transcendently misconceived as Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip.

Of the many iconic moments of unintentional hilarity to be found in Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, none is more infamous than the scene from “The Wrap Party” where Tom Jeter (Nate Corddry), a cast member of the titular show-within-a-show, leads parents with a strong, stoic “American Gothic” vibe on a tour of the historic studio where his show is filmed. The painfully earnest young man hopes to impress them with his success and the show’s rich tradition, only to have his father respond to his son’s prissy assertion that they were “standing in the middle of the Paris Opera House of American television” by sarcastically yelling, “Well that’s swell, Tom, but your little brother is standing in the middle of Afghanistan!”

By that point, it has already been established that Tom’s parents don’t know who Abbott and Costello are and have never heard their “Who’s on First” routine. Yet that somehow does not keep their insufferable boob of a son from talking about the Paris Opera House as if it were a reference with deep meaning to them both.

The “Your little brother is standing in the middle of Afghanistan!” line embodies everything that made Studio 60 both mesmerizingly terrible and weirdly irresistible in one eminently quotable exchange.

When it comes to unintentional laughter, “The Wrap Party” offers an embarrassment of riches. I’m focusing on Tom and his parent’s plotline here, but “The Wrap Party” is also the episode where Eli Wallach shows up as a senile old writer to teach everyone about how the blacklist was bad. It’s also the episode where D. L. Hughley’s character goes to a comedy club to see a black comedian he’s interested in as a potential writer and is so horrified to be in the presence of sub-par humor that he looks like God won’t stop punching him in the dick.

We open with Tom understandably anxious that he won’t be able to impress his parents with his job MAKING LOTS OF MONEY BEING ON A HIT TELEVISION SHOW because, as he tells his colleague Simon Stiles (Hughley), “They don’t know what I do for a living.”

Tom’s motormouth flibbertigibbet mom and scowling stoic dad do not seem to have ever met a black person before, either. When Tom introduces his folks to his black castmate, his mother gushes that she shouldn’t be saying anything, but she thinks Dad has a bit of a crush on Halle Berry.

When Tom responds with mortification at the idea that his black colleague has a personal connection to Halle Berry just because they’re both black, Simon is quick to judge him harshly, scolding of the man’s glowering, unpleasant, possibly racist papa, “He works for a living. Don’t be an ass.”

It’s a line that reflects Sorkin’s disingenuously bifurcated take on Tom’s parents and common people in general. The suspiciously oblivious Studio 60 cast member’s parents are simultaneously one-dimensional, mean-spirited caricatures of folks from the flyover states and the simple, God-fearing men and women who make our nation great.

Sorkin is like an oily politician in that regard, perpetually waxing poetic about the greatness of a common man he looks down on from a place of unearned superiority.

Tom’s parents know nothing about comedy history, but that’s okay in Sorkin’s book because he probably works with his hands, and she probably belongs to the PTA or something. Consequently, they are real Americans we should respect and value. You know, like JD Vance.

Every bit of trivia Tom lovingly recites is met with blank faces of non-recognition from salt-of-the-earth philistines who wouldn’t know the difference between commedia dell’arte and the Blue Collar Comedy Tour. Tom’s parents seem simultaneously bored, confused, and unimpressed by everything he’s saying, but that doesn’t keep him from prattling on all the same, as if an hour in, he’ll start talking about Ernie Kovacs, and a look of recognition and surprise will unexpectedly dance across his parents’ now-impressed faces.

As the thundering climax of his tour through his workplace’s storied past, Tom attempts to dazzle his folks with a bit of information he’s certain will astound even comedy-hating half-wits like the people who raised him: it was in this very building that a comedy duo named Abbott and Costello recorded a routine called “Who’s on First?”

Not only are Tom’s folks implausibly unfamiliar with Abbott and Costello, but they’re vaguely insulted by the notion that they should know about a piece of Americana as deeply woven into our national fabric as Citizen Kane or Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

In dialogue that betrays just how often Sorkin forgets how human beings think, talk, and behave, he has Pops grouse of “‘Who’s on First,’ “You say that like it’s famous,” and Mom insists, “Honey, Dad and I don’t watch Comedy Central.”

Funny people know how to read the room and their audiences. Yet, learning that his parents are unfamiliar with one of the most famous routines in comedy history doesn’t keep Tom from continuing with his lengthy spiel about comedy that’s roughly ten thousand times more obscure than “Who’s on First?”

When Tom’s mother has the audacity to refer to the noble art form of Tom and his colleagues as “skits,” he can no longer hold his tongue or conceal his rage.

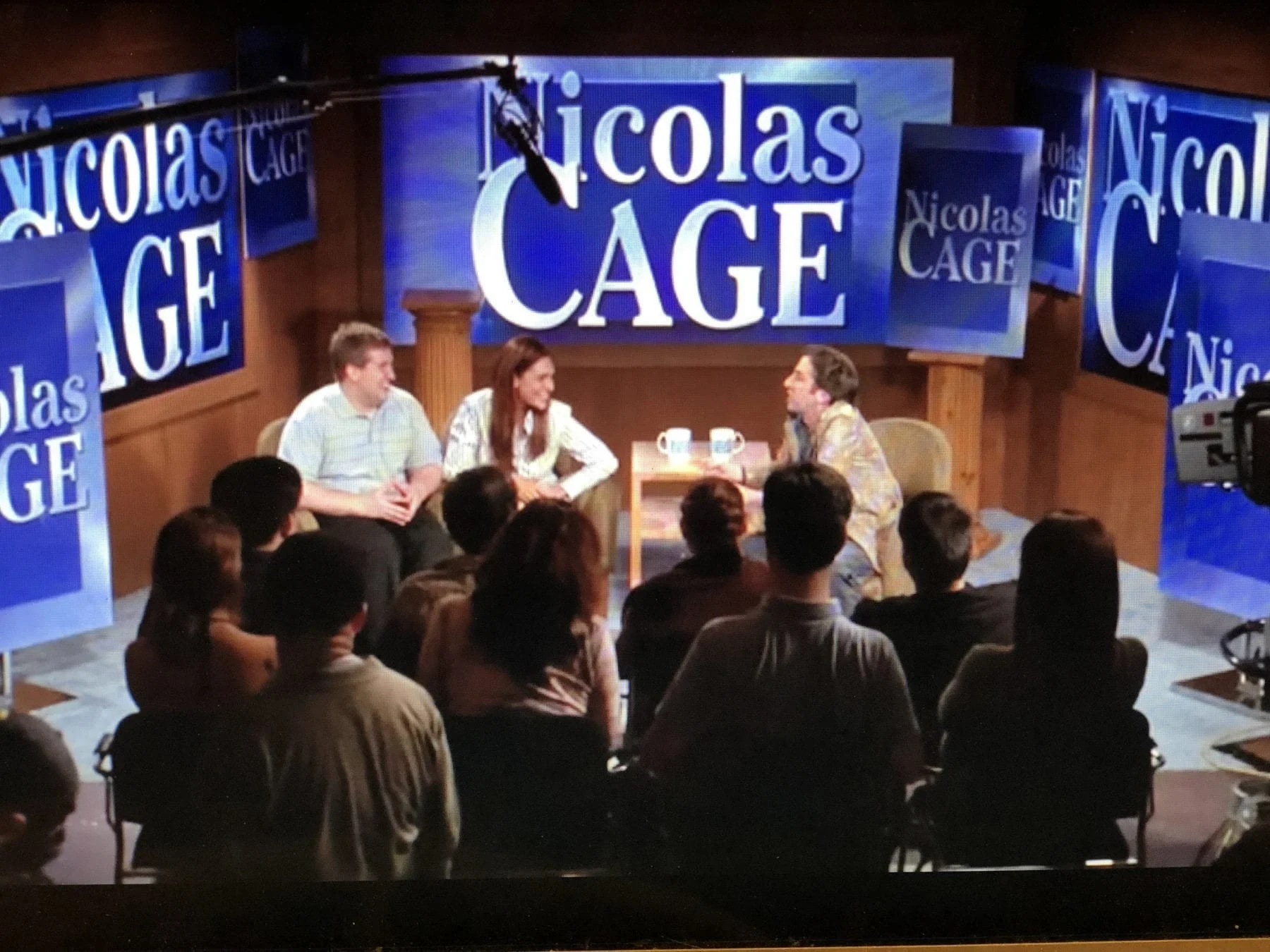

Voice quivering with wildly misplaced outrage, Tom snaps, “We don’t do skits, Mom! Skits are when the football players dress up as the cheerleaders and think it’s wit. Sketches are when some of the best minds in comedy come together and put on a national television show watched and talked about by millions of people!”

Equally overflowing with unearned self-righteousness, Daddy hisses, “Don’t you talk to your mother like that!” This leads directly to the most deliriously, deliciously insane moment in an epic boondoggle full of them, the aforementioned exchange wherein Tom angrily spits back, “I’m trying to tell you you’re standing in the middle of the Paris Opera House of American television!” and Dad hollers defiantly in return, “Well, that’s swell, Tom, but your little brother is standing in the middle of Afghanistan!”

It’s a line that stops the scene and the episode cold, an absolute humdinger of a doozy that exists because seemingly no one was willing to say no to Sorkin or tell him that he’d lapsed irrevocably and entertainingly into self-parody.

Tom’s pop may look down on his son for being a rich, famous millionaire entertainer instead of a real man like his soldier brother, but he discovers there are upsides to wealth, fame, and power, like Tom being able to send body armor to his sibling and his fellow soldiers (real, patriotic, hardworking Americans, Sorkin would condescendingly and half-heartedly insist) to use.

This at least has historical precedent, as John Belushi famously armed several Navy SEAL teams personally out of his Saturday Night Live salary during the late 1970s. The “Bluto Brigade” was known and respected everywhere.

Sorkin is such an insufferable centrist that he has Tom use his personal fortune to send supplies to his brother and his fellow soldiers in Afghanistan. Motherfucker is helping out THE PENTAGON while uplifting the soul of a nation with his artistry.

Tom’s story does not end with the most notorious dialogue in all of Studio 60. With cloying sentimentality, Sorkin attempts to engineer a fragile peace between these warring caricatures of huffy show-business arrogance and middle-American ignorance.

When his parents get into their car and prepare to drive back home, Tom asks his dad if he has a turntable. The man grouchily insists that he doesn’t need one of them newfangled CD players.

Confident that introducing his father to the concept of “comedy” can only bring them together, Tom gives his father an LP of “Who’s on First?”

In a wholly unearned burst of treacle, Tom tearfully tells his comedy-oblivious old man, “I love you, Dad, and whether you like it or not, you taught me everything I know.”

It’s supposed to be a tear-jerking moment of connection between two very different men whose stubborn pride drives them apart even as they share the bond of blood, history, and tradition.

Most of what Tom seems to know involves granular knowledge of comedy history from vaudeville to the present. If his father did, indeed, teach him that, he seems to have been stricken with amnesia in the interim.

The Tom and his parent’s plotline from “The Wrap Party” reminds me of Loqueesha in its stubborn insistence that comedy has the power to change society and uplift the human spirit.

Comedy does, of course, have the power to change society and uplift the human spirit, but Saville’s and Sorkin’s delusional conviction that their own brand of didactic, brutally unfunny comedy can achieve miracles doesn’t just undercut their arguments: it destroys them.

When Preston Sturges used Sullivan’s Travels to articulate the lifesaving, life-affirming power of comedy and escapism, the film was his best argument. Sturges didn’t just assert that comedy is important and that comedy matters: he illustrated it as well.

With Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, Sorkin set out to create nothing less than the Paris Opera House of American television, an enduring tribute to the righteous satirical warriors who make us laugh while speaking truth to power.

Instead, Sorkin created a laughingstock for the ages. We’ve never stopped laughing derisively at Sorkin and his epic folly. We never will. In that sense, the series has endured, albeit not in the manner its creator intended.

Did you enjoy this article? Then you will LOVE the Flaming Garbage Fire Edition of The Joy of Trash because it includes this piece and 51 more just like it!

Nathan needs teeth that work, and his dental plan doesn't cover them, so he started a GoFundMe at https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-nathans-journey-to-dental-implants. Give if you can!

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here

AND you can buy my books, signed, from me, at the site’s shop here