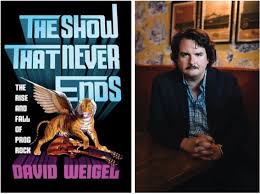

Literature Society: The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock

As you may have ascertained by now, I am a man of infinite curiosity. That’s what powers my life and my career. I want to know something about everything, whether it’s the XFL, Vince McMahon’s short-lived attempt to create an extreme alternative to the NFL, the sordid lives of hair metal and hip hop groupies or the tortured psyche of former child star Corey Feldman.

I am a man of infinite curiosity. Books are essential because they satiate curiosity, they expand your knowledge, they make the world at once more wondrous and mysterious and more knowable. That’s one of things I love most about my wife: we share a curiosity about the world so vast not even our voracious consumption of books can satiate it.

So when I saw that ace Washington Post journalist Dave Weigel had written a book on progressive rock, I was delighted, because I like Weigel as a writer and human being, but also because progressive rock is something I somehow made it forty-one years on the planet without knowing anything about.

I didn’t know anything about progressive rock because the books that I read growing up made the genre seem not just pretentious and bloated but borderline unlistenable, like a punishing endurance test rather than a treat. That’s supposedly true of the music of Phish and Insane Clown Posse as well, and if I hadn’t written a book about those groups I probably never would have listened to them either. Conventional wisdom sure can be boring.

Rock and roll conventional wisdom, for example, posits progressive rockers not as heroes who pushed an art form forward through experimentation and ambition and virtuosity but rather as the pompous, pretentious villains who nearly destroyed rock music by moving it away from its minimalist roots and into a realm of humorless pretension.

Prog rockers were easily and convincingly caricatured as long-haired men with no discernible sense of humor or modesty who performed hour-long suites about orcs and elves on Mellotrons when not delving deep into the world of complicated time signatures, or covering Bach.

I grew up thinking that prog rockers were guilty of the greatest musical crime in all of music: taking themselves too seriously. In trying to elevate the art form beyond its sweaty, visceral roots, they were instead destroying rock and roll by weighing it down with pretension and theory and an emphasis on virtuoso playing instead of energy and enthusiasm. Or at least, that’s how the story is supposed to go.

In this reading, punk rock was not just an answer to progressive rock but an antidote to it. Prog rock pretension was the disease: feral punk rage was supposed to be the cure. If progressive rock was all about brilliant technicians performing endless solos, punk prized crudeness and energy. Progressive rock was the exclusive realm of musicians who prided themselves on professionalism. Punk was supposed to be the authentic music of kids who could barely play their instruments: Prog was the music of people who, if anything, played their instruments too well, and for too long.

There’s undoubtedly an element of truth to this, but like most widely accepted historical narratives, it’s way too tidy, and way too neat. Weigel illustrates that in its own way, prog rock was rebel music. It was the music of people who, like the punks that came after them, were bored and dissatisfied with popular music, and almost accidentally created a new scene and a new world and a new way of approaching both music and art.

Technology plays a crucial role in the development of prog rock. The oft-derided sub-genre is defined by its emphasis on virtuosity and experimentation, its love of concept albums, lunatic ambition, and unusual time signatures, but it was also defined by its pioneering and adventurous use of synthesizers and Mellotrons and other early electronic instruments that expanded the sonic possibilities of pop music.

Prog rock evolved and de-evolved like countless other movement, with a collection of ambitious, iconoclastic young men (not surprisingly, prog comes off as an overwhelmingly male art form, both in terms of the performers and the fans), many British, separately exploring the same kinds of ideas involving expanding the parameters of rock by implementing elements of classical music, jazz and avant-garde theater. Prog rock is a genre of ideas, the bigger, broader and more ambitious the better.

These were men like Peter Gabriel, a shy, sensitive artist (in the most highbrow, pure sense) who became something else onstage, a brash, flamboyant performer seemingly as rooted in theater, clowning and performance art as rock and roll music. And then there’s the brilliant guitarist and innovator Robert Fripp, whose enormous, albeit justified ego (he clearly thought he was God, and when he was in the zone creatively, could certain pass for at least a minor deity) and big swinging dick of a guitar became one of the primarily catalysts for prog’s strange, halting rise and fall.

I love reading about rock and roll because I am inherently fascinated with assholes and narcissists and exquisitely unselfconscious people who have no idea that the world views them differently than how they see themselves. The Show That Never Ends is full of that kind of toxic rock star ego, but the asshole excesses of the prog rock brigade were unique.

Despite progressive rock’s less than stellar current critical reputation, Weigel illustrates that for a while at least, progressive rock was both obscenely popular and critically respected. Albums with 23 minute-long songs about man’s place in a seemingly random and cruel universe and classical music covers shot to the top of the charts and were performed in sold-out shows throughout the world.

With prog, rock got highbrow. It got educated. It went to college and immersed itself in the heady world of classical music, fantasy fiction and avant-garde jazz, with its complicated time signatures and emphasis on adventurous, experimental playing. And it exploded worldwide, including Canada, where Rush used the genre’s obsession with ideas to agitate on behalf of the Objectivist worldview of Ayn Rand.

Then things took a turn. The world seemingly fell out of love with Prog just as quickly and permanently as it fell into it. Peter Gabriel departed Genesis and apparently took all of its artiness, pretension and theatricality with him, since in his absence the group morphed unmistakably into an undistinguished pop band, albeit a very successful one.

The same was true of Yes. During the prog years, the group loomed large but like a lot of prog groups, they lost their confidence when the album and ticket sales started to die off and churned out radio-ready hits that sounded nothing like the music that made them famous, most notably the mainstream hit “Owner of A Lonely Heart.”

Some of the book’s most fascinating passages chronicle the post-boom period where the increasingly desperate standard-bearers of prog rock would seemingly do anything to remain in the game. For Yes, that meant dealing with the absence of key members Rick Wakeman and Jon Anderson by enlisting New Wave duo the Buggles (the one-hit wonder that kicked off the MTV revolution, appropriately enough, with “Video Killed the Radio Star”), who were recording at a studio next door to Yes, to become forty percent of Yes 2.0.

So while some of prog’s biggest stars abandoned the genre in search of mainstream success, sometimes finding it, a second wave of prog groups like Marillion were proudly flying the prog rock flag even after the music had become deeply unfashionable. Prog remains deeply unfashionable and un-hip. Hopefully this book will help change that.

Weigel’s book has forever changed the way that I look at prog rock, although I must say that I’ve never really given it much thought. I lazily bought into all of the stereotypes and cliches and snark but now I feel like I’ve misunderstood and underrated the genre. It’s a whole world onto itself, a lost world Weigel captures vividly and concisely.

The Show That Never Ends is exactly what I was looking for: a compelling, lean and page-turning exploration of a fascinating and misunderstood scene. Given the subject matter, it’s a little ironic that my main criticism of the book is that it simply isn’t long enough.

Support Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace